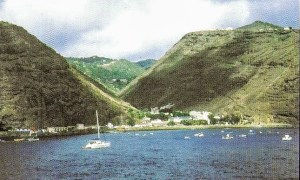

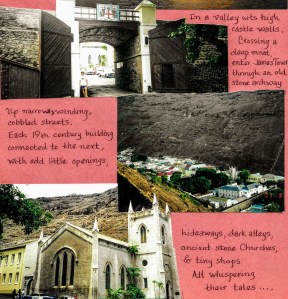

Cape of Good Hope, also known as the Graveyard of Ships, became a distant memory along with prayers of gratitude for light-moderate conditions as we spent the next 14 days sailing 1,500 miles across the South Atlantic. After anchoring in James Bay, Jerry and I dinghied to a high wharf and walked into a history book. Castle ramparts kept guard as we crossed a moat, scampered beneath an old stone archway, and entered Jamestown.

Winding cobbled lanes were lined with 19th century establishments and tiny shops, all scrunched together—except where odd little openings and shadowed alleys beckoned with anecdotes from the olde world. Locals welcomed us with smiles and greetings as we made our way to eat at Anne’s Place set in the Castle Gardens. Amid the endemic flowering ebony plant, pines, ferns, and other colorful foliage, we dined on fishcakes, although the pumpkin stew sounded interesting. Over lunch we ruminated about some of the famous visitors over the centuries who traversed this intriguing land—Naturalist Charles Darwin, astronomer Edmund Halley, Captain William Bligh (think Mutiny), explorer James Cook, and exile Napoleon Bonaparte.

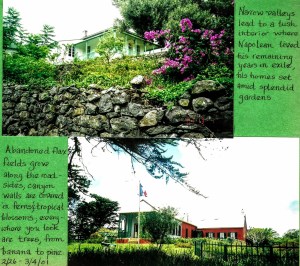

The following day we rented a car and toured the 47 square mile island with cruising buddies. Zigzagging our way along narrow roads and through quiet tidy villages with beautiful gardens and groves of mango and avocado trees, it was a surprise to observe so many contrasting environments. Hilltops surrendered vistas of verdant valleys and abandoned flax fields peppered by volcanic slopes where jagged monoliths sat in watchful quietude.

Within the lush interior we encountered Napoleon’s final homes—a far cry from his lavish lifestyle, pomp and circumstance, and battle cries. For two months he resided at the Briars before moving to Longwood House. Set among splendid gardens of bougainvillea, tree ferns, and tropical blossoms, the home contained French Provincial furniture, artwork, and memorabilia. It may not have been a palace, but his remaining six years were spent in simple comfort. Bonaparte chose to be entombed by the whispering waters in Geranium Valley, although France interrupted this peaceful slumber when they moved his remains back to Paris.

Moving on, we paused at 18th century forts,archaic stone churches, and along rocky paths that often led to unidentified ruins, wondering about the untold stories hidden beneath the rubble.

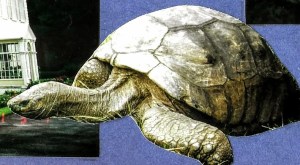

No visit would be complete without a stop at the Governor’s Plantation House to hang out with one-eyed Jonathan and other giant tortoises. Approximately 200 years old! He’s seen the upheaval of several governments, turmoil and heartache of wars, and gradual transformation into a peaceful country now under British rule. The tales he could tell—if only he could talk.

Along the coast near Jamestown bronze-hued cliffs, carved by centuries of crashing surf, are an impenetrable fortress with a 1,000 foot drop to the ocean. History seeps between the cracks of stone walls that line trails to ancient crumbling barracks and lookouts.

Huge cannons lay abandoned, reminders of wars fought and lives lost since the discovery of this island in 1502 by Portuguese explorers. Today one can gaze out to sea and not look upon warships, but whale sharks, humpbacks, and pan tropical spotted dolphins. Seabirds circle above, diving towards a flash of silver, a salty treat. If you’re lucky, you’ll catch a glimpse of the St. Helena plover, aka the Wirebird, due to its long wiry legs.

One final tidbit—Up until 2017 St. Helena could only be reached by boat. Now there’s been a new invasion, the modern world of commercial airlines and cruise ships. Hopefully the tourist industry won’t destroy the quaintness and tranquility of this island in the middle of nowhere.

History is a gallery of pictures in which there are a few originals and many copies—Alexis de Tocqueville, former Minister for Europe & Foreign Affairs of France (1805-1859)